I don’t remember when, but I think I was talking about adaptations in one of my reviews. I distinctly remember making a reference to people trying to adapt a poem from a sculpture, or something stupid like that. I’m gonna talk about that shit in this DOUBLE FEATURE review for Let the Right One In and its American remake, Let Me In.

Two Films, two adaptations, one book

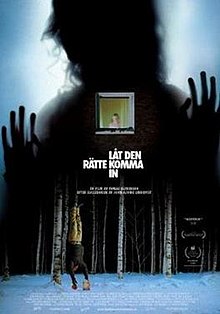

Let the Right One In, or, LTROIN, or the first one, is a Swedish film, which is, ironically, based on a fucking book. The first one is an adaptation. But. I do not read. I simply do not read. I used to read. I used to read 8 hours a day. I used to read more than anyone else in my local library’s summer reading competitions. I used have no friends because I read so much. I read the entirety of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings in its unabridged glory. For fun. For fun. I used to read. Now, I get laid.

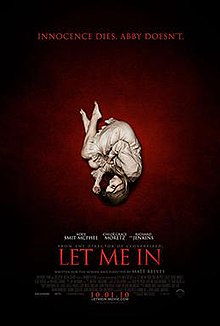

Nevertheless, the first one is based on a book, but I’m not going to talk about it much because a) this is a film review blog and I want to stay on brand and b) see above tirade about when I developed astigmatism and lost my virginity to a really hot, sexy, woman with big boobies who totally, totally orgasmed. The American remake, directed by Matt Reeves (with cinematography from Greig Fraser), Let Me In, or LMI, or the second one, is the adaptation in question. I saw the second one before the first one because I am a boring, stupid American who can’t be fucked to give international film an honest try. But also because when I googled, ‘scariest films on Hulu’, the second one was on a list, but the first one was not. So who’s really a racist, me or the guy who wrote the internet list? Checkmate, libtards.

Let Me In, or Why Matt Reeves is a Voyeur

K so if you recognize the name Matt Reeves, it’s because you may have seen a little-known Indie venture funded by Warner Brothers. Maybe. And I may have seen it twice and I may have been more interested in its style vs its substance. Maybe.

Matt Reeves made The Batman.

There’s more. Do you recognize the name Greig Fraser? I talked about him in my review for Killing them Softly, and I totally fucking mentioned his connection to… drumroll please…

Matt Reeves’ The Batman.

Sidenote. Fraser is an incredible cinematographer and he is solely the reason why all three of these films have such a striking visual feel. The second one is a crisp, colorful but focused experiment, and a collaboration with Reeves that sets the tonal and directorial groundwork for The Batman in many, many ways.

The second one has a lot- a lot– of similarities with the bat movie. Both films feature a murderer who wears a weird gimp mask who stands/sits behind their victim for an ominous, extended amount of time to prolong tension. Both films feature an out of place voyeuristic element that plays no real part in the characters, but does play a role in earlier iterations of the character. Both films demonstrate an odd, juvenile male sexuality. Let me explain.

The first, more obvious similarity is that Reeves’ the second one features a man committing murders while wearing some sort of shiny, homemade mask that mainly reveals the eyes of the murderer. It’s reminiscent of a sexualized gimp mask, and this visual element is heavily featured in Paul Dano’s Riddler. It’s a new development considering the Riddler is not traditionally shown wearing a mask like this in the comics or other films. It’s a direct homage and holdover from Reeves’ work on the second one. In fact, this particular image may come from the first one. The Swedish version of this film has a couple of frames where the protagonist flips through his little book of crimes and there’s a newspaper clipping of a man in a mask with its eyes cut out, holding a knife. Can it be that Reeves is… not original??

A deeper similarity is the voyeuristic visual elements. This character trait is one of the first we see in the second one’s protagonist, named Owen. He dances in his room, wielding a knife and threatening an imaginary antagonist. Then, he grabs his telescope and spies on his neighbors. One is an older boy who’s strong and works out, the other is a couple- and a woman’s breast is revealed. She sees the boy, and closes the shades. Hey, remember that weird sequence where the Batman spies on Catwoman while she changes? Or, more obviously, remember the opening sequence, where someone (implied to by the Riddler) spies on the mayor and his family in The Batman? Regardless of the nonsensicality of having both the Riddler and the Batman having a voyeur sequence, you cannot deny that this is a really, really weird addition to the second one– because the first one does not have a specifically voyeuristic protagonist. That’s pretty new (there’s a quick, throwaway scene in the second one where the protagonist does a little staring, but I have to come back to that later). The addition of this voyeurism that’s explicitly present in both films is a weird one, considering it adds nearly nothing to both films, and, in fact, serves to confuse and conflate audience expectations in The Batman (I will grant that perhaps making both the Riddler and the Batman be voyeurs was a way to draw similarities between the two, but I’m not so convinced that that’s the case).

The most subtle of the similarities between Matt Reeves’ the second one and The Batman is the fact that the protagonists in both of his films are sexually immature. Let’s start with the film that more people have seen to explain this. Bruce Wayne is a weird, lonely, gothic emo boi. He struggles with people, doesn’t really socialize, and responds awkwardly when Selena Kyle kisses him. Further, he becomes weirdly aggressive and accusatory when he thinks that Selena Kyle may be sleeping with Falcone. He only softens up when he realizes that his accusations of Selena are unfounded, and that Falcone is her father, but this weirdness is not addressed or resolved. Now, for you children, who have not had complex emotional relationships with women, or do not yet grasp that women have their own autonomy, sexuality, values and lives, let me explain. Just because women have sex with someone that is not you (or the protagonist), does not make them lesser in value, less viable, or sluts. It makes them normal. Reeves’ Wayne exhibits a type of jealousy and insecurity that is symptomatic of people who think that female sexuality is a deviancy, and that it is shameful in some way. I don’t know if this is what Reeves intends, but you can’t really deny it when it appears in the second one.

By the way, if, at this point, you’re wondering what my qualifications are regarding women and why I, as a man, should be allowed to speak for and regarding female sexuality, then I shall have you know that I have had many sexes with many women. I have delivered many orgasms, and I am a dick god who has had many successful and repeated sexual encounters with my massive, massive, penis aka cock. Also, I don’t call women ‘females’.

Europeans and their Nude Beaches and Public Boobies: Explained

Both of these films feature children, and the second one stars the incredibly talented Choe Grace Moretz and Kodi Smit-McPhee, who were in Kick-Ass and X-Men: Days of Future Past, for those of you who only watch superhero movies. In this film, having an immature, juvenile sense of sexuality is acceptable, even characteristically expected. Owen watches a mature couple initiate sex in the second scene of his film through a telescope, later he spies on his friend when she changes (she’s got the body of a child). He does not understand anticipate the fact that relationships (when he asks to go steady) involves a sexual aspect- in fact, he’s naked in bed with a girl and does not react the way you’d expect someone to. So, this begs the question. Is Reeves’ depiction of voyeurism as a symptom of sexual immaturity a selective decision to characterize the protagonist? Or is it simply Reeves being a fucking weirdo? As much as I enjoy being a bully, I’m not going to lie, I think that it’s the former, not the latter.

That is to say, I want to believe that Matt Reeves uses this element of voyeurism to demonstrate immaturity or some form of deviancy in his characters, rather than a breakthrough of his own sexual deviancy, akin to Quinten Tarantino’s infamous foot fetish. Is it effective? Sure. Is it repetitive? Yes. Is it original? Not exactly. Again, like the gimp mask being a few throwaway frames in the first one, being featured in Reeves’ the second one and The Batman, I think that the voyeurism may be a holdover of a few seconds from the first one that permeated through Reeves’ two films.

Adaptations reveal more about you than the adaptation itself

Matt Reeves Introduction, or perhaps underlining, of the aforementioned visual elements leads the way to a discussion regarding remakes and adaptations. I’ve been working (unsuccessfully) on a really lengthy and, franky rambling, discussion of Indian films, their values and how they present themselves in Indian adaptations of American films. Maybe I’m racist, but I’m actually finding an easier time of talking about adaptations when talking about an American adaptation of a Swedish film. The American Let Me In is shot for shot almost the same film as the Swedish Let The Right One In, from the framing, to the plot beats, to the dialogue to the very title. It’s nearly exactly the same film. The few differences- and there are some distinct differences- give us a very clear insight into what it means to make a film with a good story for specific audiences, how to identify which elements of the story are core to the story itself, and which parts you can or must change to appeal to your target audiences.

That is to say, these two films allow us to figure out what part of a story is crucial and defining, and which parts of a story can be added, modified or outright removed in order to create a far more appealing film for an intended audience. The skill it takes to identify these moving parts may be why Matt Reeves was selected to adapt DC’s The Batman.

After a middling portrayal of Batman by Ben Affleck and the action-centric depiction of Christian Bale’s Batman, Reeves’ detective Batman is a more accurate depiction of The World’s Greatest Detective than any other film depiction of The Dark Knight. Regardless of how the story is derailed at the halfway point, I think that Reeves’ Batman is the truest adaptation of the comic book hero- far truer than Affleck’s gun toting egomaniac and even Bale’s (arguably iconic) role.

The first one names its main characters Oskar and Eli, a young boy and a visually depicted girl. The second one names its main characters Owen and Abby, of the same exact age- down to the day. Both films feature identical plots. A boy watches an old man and a young girl move into his building, he hears them through the walls, and befriends the girl in the apartment complex’s playground in the winter. The girl smells funny, solves rubik’s cubes overnight, and is not affected by the cold. The girl’s caretaker fails in an attempt to murder and retrieve a jug full of blood. The girl is forced to lure a man into a tunnel, manipulate him into caring for her, and kill him. The old man fails in the next attempt to retrieve blood for his vampire ward, and burns his face with acid in order to protect his identity- and hers. The boy, encouraged by his new friend, stands up to his bullies, engages in strength building with his male coach, falls for the vampire girl, accepts her for who she is, and eventually protects her when someone figures out what she is and tries to kill her in a bathtub. Both films end nearly identically, when the boy in a train, the girl in a large suitcase by his feet, communicating with him via morse code.

Mythologically, there’s some understood magic that binds men to vampires as their familiars. In the book, it’s because the old man is a pedofile and can have sex with the body of a girl in exchange for murdering people for her to suck their blood. In the films, the old man any AbbyEli’s relationship is not explained as such. Neither Swedes nor American audiences would be particularly happy with their female lead endorsing pedofilia, nor with their films depicting it. The first one works around this by showing Oskar’s disturbed, violent “I’m going to shoot up the school” vibes to a near maximum. Oskar has a book full of newspaper clippings of crimes, has a knowledge murder details, and has an affinity for violence, depicted by his violence towards his imaginary friends throughout the film. The American the second one veers from this psychotic behavior in the second half of the film, until the end. Owen stops trying to stab trees, he does not possess a book of grizzly murders, and he has no intentions of murdering the man who finds his vampire girlfriend. In the end, however, in a diversion from the first one, Owen seemingly reaches for the man who discovers Abby, but actually closes the door on them, allowing Abby to feed in privacy, and condemns the man to die alone on purpose. Conversely, in the first one, Oskar simply walks away, and actively rejects the murder by dropping the knife.

I don’t know if I support or oppose either depiction. I don’t know if it’s better that the protagonist devolves from a lonely, disturbed kid with daddy issues to a kid who can actively ignore a grizzly vampire murder. I don’t know if it’s worse that the protagonist at the end cannot stomach the violence and rejects it, by dropping his knife and turning away from the man’s death. However, I think that Reeves’ version works a little better, considering that a kid would only abandon his life if he was truly committed to the vampire lifestyle. If there was some mystical reason why the kid was bonded to the vampire, then it wasn’t really shown in either film- a subtext perhaps lost in the adaptation from the richer text of the book.

American pearl-clutching

There’s another, pedofilia-related element that highlights the difference in shock factor between international (or just Swedes) audiences and American audiences. In the first one, there’s a scene where Eli changes after a shower. Oskar peeks inside the room, and quickly turns away. This is the only time Oskar demonstrates voyeurism in the film. In the second one, this is just a habit that Owen has- of watching women in moments of intimacy- and it is not the first time he spies. Is Reeves’ buildup and payoff of Owen’s voyeurism a better decision than the first one’s single depiction? Perhaps. But perhaps it needs the build up, considering the single scene of Oskar spying in the first one is an incredibly graphic scene. Rather than the camera simply watching Oskar as he pushes open the door, and his eyes widening at the first time he sees a naked girl, we actually see what he sees- a very explicit, but quick, shot of Eli’s vagina. This feels gross to type out.

In no cases would a shot like this ever be ok in any American media. American culture is adamantly and vehemently against any sexuality or depictions of sexuality of anyone under the age of 18- especially women. Is this some ramification or puritanical, overtly religious beliefs that have permeated American society? Yeah, definitely. Our age of consent is understood to be 18, and in movies like Transformers: The shitty one you can’t remember; no, not that one, the other one. Yeah that one, we even get a weird sequence where a twenty something boy defends his relationship with a 17-year old girl- and we all thought it was weird. Americans hate hate hate sexualizing minors. The half-second shot of a 400-year old vampire’s 12-year old vagina was not ok at all. So maybe that’s why Reeves chose to dig into Owen’s voyeurism to dig into the subtext to work around this shot and avoid audience backlash. Or maybe Matt Reeves is fuckin weirdo.

Matt Reeves fails the Bechdel Test

A big reason for why I’m still casting doubts on Matt Reeves is because another choice (or series of choices (or theme of choices)) he made involves the value of women and their autonomy in his stories. The Batman features three women: one of whom is crazy, two of whom die, and the third is a cat lady. That’s perhaps an oversimplification, so let’s instead talk about mentions of girls and women in the second one. Owen is continuously accosted by three bullies, who attempt to belittle him by calling him ‘a little girl’ over and over again. They attempt to emasculate and humiliate this boy by misgendering him, despite there being no reason to. The bullying is nonsensical, and largely in line with how bullying generally is. But in the first one, the bullies actually call Oskar a ‘pig’. Maybe this is a translation or subtitle issue on Hulu, but my understanding is that the bullies did not initially use Oskar’s gender as an insult. Why the change? Why is calling someone a woman more insulting than calling them a pig? Further, the first one has actors for Oskar’s parents, who are there physically, but play no real part in the story. His mother is more active in his life- telling him not to leave the courtyard after the first murder, or by scolding him when he gets into a fight- but is ultimately not an active character. Reeves’ the second one does not even have a father on screen, the mother’s face is never shown, and her effect on the film is similarly subtextual.

When Abby murders the man in the tunnel to feed on him, she simply gets up and runs away. Eli, on the other hand, kills her victim, and then shows a moment of remorse. Reeves’ depiction of the female vampire is subtly less sympathetic. Abby bites, but does not kill a woman, and this woman is accidentally killed later when the curtains open in her room and she spontaneously combusts, killing a female nurse at the same time. In the first one, the woman is aware that she is now a vampire and chooses for the curtains to be pulled and for the sunlight to kill her. In this, Swedes version, the nurse is a man and he is not killed in this sequence. So why the culmination of female-centric antagonism, violence and absenteeism?

Am I implying that Reeves holds some amount of hatred, misunderstanding or disdain for women? Am I trying to say that Matt Reeves is a creep? A weirdo? What the hell is he doing here?

Again, I want to err on the side of giving the guy the benefit of the doubt. A nihilistic portrayal of Abby and Owen isn’t a bad one- considering Abby is a murderous vampire and Owen is some disturbed weirdo, and when he elects to live with her and help her survive by allowing her to murder people isn’t exactly a good choice. It thematically makes a bit more sense than Oskar begrudgingly or unwittingly falling for the vampire’s magical allure. Further, it’s a subtle nod to American sensibilities, where they’d rather have the child be a murdering lunatic than a disturbed 12 year old boy who is manipulated and coerced into serving a far older individual- a reversal of who’s taking advantage of whom.

Which version is better?

You’ll find that on Reddit and other film forums, people are fairly split on which version they prefer. Some people like the Swedes’ details, some people enjoy Fraser’s unique cinematography. There’s no wrong answer. I point out a lot of the major changes between the two films, but again, they’re otherwise identical. The framing, the plots, the characteristics are all very nearly the same. In both films, Oskar/Owen values physical strength as a valuable trait. In Reeves’ version, it is because spies on his neighbor who works out, and that’s why he chooses to engage in weight training. Oskar chooses weight training because he likes being able to physically dominate people. In Reeves’ version, the bully is a victim of his older brother’s explicit bullying, but in the Swedes version, the older brother’s bullying is not explicit.

I have rated both films a 7/10. Chloe’s acting is fucking brilliant and I now want to go watch her in other works, I really like Fraser’s cinematography, and I really enjoy bullying Matt Reeves for being some sort of virgin, so I give Let Me In the edge- but again, maybe it’s just because I’m racist against people who aren’t Americans.